USING AN INSTANT POT AT HIGH ELEVATION

I recently joined the Instant Pot or pressure/multi cooker craze, and have found a whole new world of recipes, reviews and self-proclaimed experts. I certainly don’t consider myself an expert, but after about a year of research and trial-and-error, I’ve got experience that may be helpful to the newbies.

My Instant Pot Ultra was purchased in December 2019, and most of my experience is based on this model. There are a lot of different multi-cookers out there to choose from, and a lot of websites touting pros and cons. Most websites are NOT run by people who actually live at high elevation, and hands-on experience at high elevation is hard to find on the web. My first purchase was the Mueller Ultra Pot, which I chose after comparing it with the Instant Pot Duo SV, which was currently on sale at Costco, and a couple of other popular Instant Pots. After about a week of use, I returned it, did a LOT more research about these multi-cookers, about using them at high elevation, and about high-elevation cooking in general. After a great deal of consideration, I chose the Instant Pot Ultra, 6 quart, and I’m glad I did. If this model is not available at the time of reading or it is not offered at a competitive price, look for some of the features below in the most current models.

HIGH-ELEVATION CONSIDERATIONS

At high elevation, we have a few special needs to keep in mind when using these multicookers. Some are often mentioned on various websites promoting them or on those providing recipes. Others are not.

TIME ADJUSTMENT

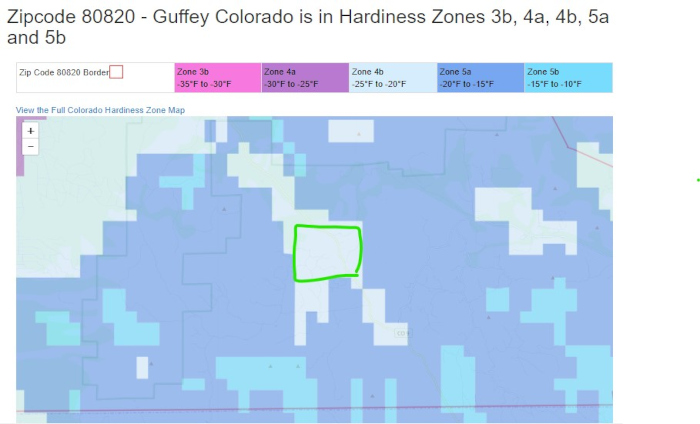

It is pretty well known that at high elevation, we need to adjust all multicooker recipes according to our elevation. There are charts available on several websites. Generally, the consensus is that for high elevation we should increase pressure cooking time by 5% for every 1000 ft above 2000 ft elevation. So for me, at 9,000 feet, I need to add 35% more time to every recipe. For example, if a recipe says you’ll need pressure for 20 minutes, I’ll need to multiply 20 times 1.35 = 27 minutes. This method has worked well for most recipes, but be prepared for some trial-and-error. For some recipes I add less time, for others I find I need more time. I cannot say for sure, because I have no hands-on experience at lower elevations, but I believe that on the upside, the Instant Pot actually takes less time to come to pressure. Because water boils more quickly at higher elevation—the same would be true under pressure, because the pressure added by the pressure cooker only ADDS it to the atmospheric pressure we are already in, outside of the cooker.

HIGH ELEVATION SCIENCE

This article at HipPressureCooking explains a bit of the science involved. It took awhile for me to wrap my head around all of this, and this article at ScienceABC helps explain how water boils at high elevation. The short version: Water boils at a lower temperature at higher elevation. It boils more quickly at higher elevation. The temperature of boiling water never gets any higher that what your elevation allows for, therefore the food will take longer to cook. Adding pressure inside a pressure cooker allows water to boil at a higher temperature than it would in an open pot, therefore the food cooks faster under pressure.

HIGH PRESSURE VS LOW PRESSURE

Most of the Instant Pots boast their HIGH Pressure is around 10.2-11.6 psi (let’s call it 11 psi). At sea level, this adds the 11 psi to the atmospheric pressure of 14.7 psi, for a total of about 25.7 psi in the pot. LOW pressure is listed as 5.8-7.2 psi (let’s call it 7 psi), so at sea level the pressure inside the pot would be about 21.7 psi.

Here at 9,000 feet, the atmospheric pressure is about 10.5 psi, so after doing the math, HIGH pressure here is roughly 21.5 psi, and LOW pressure would be about 17.5 psi. So for me, using the cooker at HIGH pressure here is about the same as someone at sea level using LOW pressure. We can’t change the pressure that these pots do, but we can keep in mind what’s going on and why we need to add more time to our recipes. When a recipe calls for LOW pressure (this is rare), at my elevation I could easily use the HIGH pressure function instead of LOW pressure with no time adjustment. I tried it, it works.

SAUTÉ FUNCTION

As I began to use the multicookers, I noticed that the SAUTÉ function can be very hot. It seemed that things were burning too quickly and I’d have to turn it down or off or add more liquid or oil to keep it from burning. This is also true when I cook in a pan on my stove—I need to keep my pan at a lower temperature to keep things from burning.

Here is where the article from ScienceABC is helpful. Keeping in mind that with lower atmospheric pressure there is greater evaporation, when I’m sautéing something like onions, the moisture evaporates quickly, leaving the drier part of the onion on the hot pan to burn. On the stove, I’ve learned to keep my burner at a lower temperature and take more time to cook things a little more slowly. The same holds true for multicookers, although some allow for more temperature adjustment than others. I’ve kept my SAUTÉ setting at “Medium” most of the time, I rarely use “High” and sometimes even the “Low” is too high.

SLOW COOK FUNCTION

As with the SAUTÉ function, the Slow Cook function on the Instant Pot Ultra also can provide some adjustments that not all multicookers provide. I found that the Slow Cook “High” setting is too high for many of my needs. When I “slow cook” I am not looking for a full rolling boil, but rather a gentle simmer. The high setting on the two multicookers I’ve used keeps things at a pretty wild boil here at my elevation. Turn it down!!! Now, whenever I slow cook I may use the “high” setting long enough to heat it up, but soon switch it to “medium” to continue the slow cooking time allowance, somtimes allowing for more time.

SIMMERING WITH THE INSTANT POT

Recently I was cooking a tomato sauce that needed to simmer for about an hour. I did not want it to boil or burn on the bottom, I just wanted a gentle simmer, uncovered. As the recipe suggested, I tried using the Sauté function at the LOW temperature setting. It was TOO HOT and resulted in a boil. (And with tomato sauce, that meant a lot of spits flying outside the pot onto my glasses and the countertop.) Then I tried using the Slow Cook function on MEDIUM. It wasn’t hot enough to simmer the sauce. I wanted a little more heat. Slow Cook on HIGH wasn’t enough either, but close.

Water boils at about 195.5° here. I’ve tried various temperatures for keeping a low simmer, and because the Instant Pot cycles itself on and off, adjusting itself to maintain the right heat, sometimes it boils a little more than I want, and other times a little less. Generally for a low simmer of a sauce or soup type of thing, I set my Ultra around 200-202°.

HOW TO CHOOSE A PRESSURE/MULTI COOKER FOR HIGH ELEVATION

When choosing a multicooker/pressure cooker, keep these things in mind. You’ll need to be able to adjust to longer times when using pressure. When not using pressure, you may want to adjust the heat temperature lower. Look for a multicooker that provides this option. You should also check to see what PSI is promised for high or low settings, and get one that allows for higher pressure. Some of the pots have time limits, i.e. certain functions will only go for an hour or two. You may need a longer time for your recipe, which may require you to reset your time at some point during the process. The Mueller Ultra Pot I originally purchased did not have lower temperature adjustment for the SAUTÉ and SLOWCOOK functions, and I was unable to keep things from cooking too hot. Additionally, the Mueller Ultra used a lower PSI for both their high and low settings, which would have required more time added when cooking recipes created for the Instant Pots. Please see my review of the Mueller Ultra.

The INSTANT POT ULTRA, which is my preferred choice, has an altitude adjustment which automatically changes the times for the pre-programmed buttons. This is a bit helpful, but honestly not much. They claim that the altitude adjustment “takes the guesswork out of recipe conversion.” Well, only if you use the pre-programmed choices. I think that their claim is misleading. I still have to do the math and make manual changes for any recipes which use the “Pressure” or “Ultra” settings, which is 90% of the time. I’m not keen on using the pre-programmed functions. However, this Instant Pot Ultra allows High-Medium-Low choices for the temperatures of the Sauté or Slow Cook functions, as well as a Custom choice in which you can set your own temperature. Additionally, it will remember which adjustment you chose last, so the next time you use the pot it will go back to that same adjustment until you change it. These things are all very helpful at high elevation. Please see my review of the Instant Pot Ultra.

If you’re considering the purchase of an Instant Pot or other multicooker, keep all these things in mind when making a choice. I sure wish I had known all of these things before my first purchase. Other multicookers may be just as customizable as the Instant Pot Ultra, so there may be other good choices available. Use a keen eye when selecting anything that boasts an “altitude adjustment” and try to find out what it actually does. The advertising buzz lines may be misleading.

COST

If you’re interested in buying one of these multicookers from Amazon, keep in mind that the prices on them may change daily. When I first purchased the Mueller, it was $60, and a couple of days later it was $75. The day I first viewed the Instant Pot Ultra, it was $80, just after Thanksgiving. A day or two later, after I’d decided to purchase it, it had gone up to $85. Later on it was $119. Keep in mind also, that if you want some of the useful accessories that are included with the Mueller Ultra, you’ll be paying some more $$ for all of these, in addition to other accessories that are nice to have. I’ve now spent about $140 on the IP Ultra and all its accessories. Some, I could do without, but they are nice to have. At minimum, plan on getting the glass lid, extra sealing rings, and a steamer tray or basket. I was fortunate to find a perfect steamer tray at my local thrift store. Other nice accessories: a set of stackable inserts for Pot-In-Pot (PIP) cooking, and a taller trivet to stack things higher (such as two halves of a winter squash). There are several other things that some people like, but I think I’m good for now!

ADJUSTING RECIPES AT HIGH ELEVATION

In addition to the Instant Pot quirks listed above, it is well to note that you need to use care in finding and using recipes. Many bloggers and website owners who write about their Instant Pots and share their recipes don’t seem to understand the need for high elevation adjustments. Many Most of them do not mention where they are located or what their own elevation is. This is sometimes true of writers at high elevation, also. This is a pet peeve of mine.

One of the web writers, Barbara at PressureCookingToday, has some helpful tips and often mentions on her recipes that she is at 5,000 feet, and that time adjustments may be required depending on whether you are cooking at a lower or higher elevation. That’s what I want to see on all the websites!

Realistically, I do not always adjust my times the full 35% that is suggested for this elevation. It depends on what I’m cooking, and it’s been a sort of trial-and-error thing. I’ll round up or down the times if I think less time may be adequate or more time might be necessary. I sometimes add more cook time just by choosing a longer, “natural” release rather than the “quick” release.

YOUR CHOICE

Hopefully my experimentation and ramblings here will help you determine whether to purchase a multicooker and how to choose one. Good luck! I’m liking my Instant Pot. It cooks some things a lot faster and cleaner that with old methods. Potatoes cook faster and with less water, and if I want to mash them I do so right in the pot without straining off any water. Brown rice cooks superbly in less than half the time it took in my old rice cooker. Meats that I would cook in the slow cooker all day are now done in a couple of hours, if that. Have fun researching & experimenting!

MY REVIEWS

For a few more details, please see my reviews for the INSTANT POT ULTRA and the MUELLER ULTRA POT.